1.

Primary and secondary effects

The first categorizations of the

health effects of climate change and health appeared in the early 1990s.

Principally these identified two broad kinds of effect, most often called

“direct” (such as from heatwaves, reduced cold or physical trauma from a more

powerful storm) and “indirect”, such as from ecological shifts leading to an

altered distribution of vectors (such as mosquitoes) or of food sources (see

tables 1,2).

Table

1. There are many

classifications of the health effects of climate change. This is one suggestion

for the most obvious, least contentious effects. All of these effects interact

with other factors, such as governance, infrastructure, technology and economic

and other capabilities.

Heat

stress, heat stroke (including occupational); heat stress resulting in

impairment of chronic diseases (e.g. multiple sclerosis, cardiac or renal

failure) or death, possible fetal abnormalities; in some cases improved

health from reduced cold

|

Physical

and or psychological harm and trauma from an intensified storm, flood, fire or

other extreme event, such as drought or a storm surge

|

Long-lasting

psychosocial effects from exposure to a climate change aggravated extreme

event including post traumatic stress disorder, depression, loss of place and

“solastalgia”

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

The burden of disease of “direct” (“primary”)

effects can be severe, as with the tens of thousands of excess deaths

attributed to heatwaves in France in 2003 [1]

and Russia in 2010 [2]. The burden from

excessive heat is likely to substantially increase, especially if the Paris

commitments are not met. Regions in which hundreds of millions now live are

forecast as at risk of large-scale human abandonment late this century,

including the North China plain and parts of the Middle East [3,4]. Looking further ahead, if urgent action

to slow climate change by accelerating the energy transition is further

delayed, substantial regions of the globe could experience wet bulb

temperatures of 35 degrees or more, calling into question the habitability of

even more some regions [5].

The burden of disease of the

secondary effects (see table 2) of climate change, particularly of infectious

diseases such as malaria, has long been forecast as significant [6]. However, although it is likely that

climate change has increased cases of malaria in some settings, especially in

highlands [7] the overall global burden

of malaria has declined substantially in recent decades, mostly because of the

increased use of insecticide impregnated bednets and more funding [8]. Note however, that such progress has recently stalled,

especially in parts of sub-Saharan Africa [9]. I am unaware of any

recent attempts to estimate the global burden of disease of malaria or other

infectious diseases attributable in part to climate change, although a recent

editorial in Geospatial Health provides an excellent summary of the key issues

[10].

Table

2. Climate

change has many less direct effects, which can be called “secondary”. Few if

any of these are controversial. These effects also interact with other factors,

such as ecological change, governance, trade, infrastructure, technology and

economic and other capabilities.

Vector

borne diseases (eg malaria, dengue fever, yellow fever, chikungunya, Zika),

non-vector born zoonotic disease (e.g. schistosomiasis, Ebola, HIV/AIDS); other infectious

diseases (e.g. gastro-enteritis, soil transmitted

helminthiases)

|

Impaired

food or water safety (microbial or toxic), reduced food diversity; reduced

micronutrient concentrations in crops (due to higher CO2 levels)

|

Allergies,

including thunderstorm asthma; asthma

|

Cardio-respiratory-neurological

effects, such as from worsened tropospheric air pollution, or from climate

change aggravated fires

|

Reduced

food sovereignty, reduced micronutrient intake, but without the threat of

starvation

|

Impact

on other chronic diseases, such as cardiac failure, diabetes

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

2. Tertiary effects

Two papers, each published in

December 1993, identified a third category of health effects, which the authors

called “tertiary” [11,12] (see table 3).

One paper stated “indirect effects are secondary, such as changes in

vector-borne diseases or crop production, and tertiary, such as the social and

economic impacts of environmental refugees and conflict over fresh water

supplies”. The other paper additionally noted that:

“There is a considerable literature on the effects of climate on

disease which focuses principally on

the primary effects of temperature on health. In relation to global climate

change, however, it is likely that the secondary and tertiary impacts will

outweigh the importance of the primary effects” [12].

This idea of a third major

category of health effect has not yet been widely accepted. A 1996 book on

climate change and health mentioned “more diffuse” effects including conflict

and population displacement, but grouped these with indirect effects, rather

than as a separate category [13]. An

assessment for the U.S. National Assessment on climate change and health,

published in 2000, identified five categories of health outcomes [14]. These were related to temperature, to

extreme weather events (storms, tornadoes, hurricanes, and precipitation

extremes); to air-pollution, and to two categories of infectious diseases. In

turn these were each divided into two kinds; related to water and food, and

vectors and rodents. This report did not discuss migration, social disruption,

or conflict, perhaps because its scope was restricted to that of the U.S.

As mentioned above, it has long

been understood that climate change can influence important social consequences

(with health effects) such as population displacement, conflict and

malnutrition. Malnutrition refers both to undernutrition (e.g. stunting,

wasting and at its most extreme, death) and, also, to obesity and other

problems associated with excessive calorie intake, sometimes (also) associated

with micronutrient deficiency. Two of these effects (malnutrition – albeit

probably meaning undernutrition – and conflict) were mentioned in the the first

article I know of about climate change and health, published in the peer

reviewed literature, a 1989 editorial in the Lancet [15], while Alexander Leaf, also in 1989, discussed both population

displacement and the possibility of increased hunger [16].

These effects may also be

considered tertiary not only because they are the least direct, but also

because of their capacity to harm health is at such a large scale. For example, the

conflict in Syria, which several experts think was contributed to by the most

severe drought in its instrumental record [17]

has displaced millions, had profound geopolitical effects in Europe, and killed

hundreds of thousands of people, including children. The health effects upon

survivors, both physical and mental, both in Syria and for those displaced, are

undoubtedly immense [18]. Of course,

climate change is not solely responsible for this catastrophe, and its exact

contribution is disputed [19,20]. The

total health impact of the Syrian conflict is likely to far exceed that of the

2003 European heatwave, particularly as much of the health harm to Syrians is

to infants, children and young adults, whereas deaths from heatwaves typically

result in a comparatively low per person loss of disability adjusted life

years, as it is primarily the already frail and elderly who die [21]. The morbidity and mortality from the

Syrian conflict due to anthropogenic climate change is likely to already be

very significant, even using a highly conservative causal attribution.

It has also been suggested that

the 2018 crisis of refugees seeking entry to the U.S. from Central America has

been exacerbated by drought (interacting with social and other environmental

factors including inequality and high population growth rates), which in turn

probably has a climate change contribution [22].

There are many other examples, already, in which climate change has been argued

to contribute to conflict, undernutrition, migration and other forms of

population displacement [23]. For example, Hurricane

Maria, which directly killed 64 people in Puerto Rico, contributed to at least 4,000 additional

deaths in the following four months, due in part to the interaction of

the storm with an already vulnerable social and physical system, with

large-scale and long-lasting damage to electricity infrastructure [24]. It also led to migration to the U.S.,

particularly by younger people and those more economically able.

Table

3. This lists

the most obvious “tertiary” consequences of climate change that will have

significant health effects. As with the primary and secondary effects, these

interact with governance, infrastructure, technology and economic and other

determinants.

Increased

hunger, starvation or famine (exceeding a reduction in nutrient variety)

|

Mass

migration or population displacement, including from climate change

aggravated events such as famine, drought, sea level rise, violence and

intolerable heat

|

Large

scale conflict (leading to physical and mental trauma, death and morbidity,

including from damaged health systems)

|

Significant

social and economic disruption, impairing health and/or health systems

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

In 2005 a paper written by health

workers, published outside the health literature, argued that the global health

effects of eco-climatic change could be classed into four categories; three

equivalent to primary, secondary and tertiary (though the paper did not use

these terms), and a fourth, which it called “systems failure”, a euphemism for

global civilization collapse [25]. This paper also predicted that the loss in

disability adjusted years for the third and fourth categories would exceed the

first two.

A figure in a chapter on climate

change and health published in 2007 in the third report of the

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) also recognized three broad

categories of health effects. It called these “direct”, “indirect” and via

“social and economic disruption” [26]. However, the text did not discuss the

third category.

In 2010 the terms (and closely

corresponding concepts) of primary, secondary and tertiary were revived, in a

paper, and later, an edited book that failed to identify the earlier use of

these terms [27,28]. Also in 2010, a report for several U.S. government

agencies [29] classified the human health consequences of climate change into

eleven kinds. These were listed alphabetically as asthma, allergies and airway

diseases; cancer; cardiovascular disease and stroke; alterations in normal

development; heat-related morbidity and mortality; mental health and stress

disorders; neurological diseases and disorders; nutrition and food-borne

illness; vector-borne and zoonotic disease; waterborne disease and

weather-related morbidity and mortality. The report discussed displaced people

(such as due to Hurricane Katrina) as a cross-cutting issue. It also recognized

the possibility of conflict, war (outside the U.S.) and extensive

undernutrition, both domestically and globally.

The health chapter in the most

recent IPCC report [30] also referred to three kinds of health effects of

global warming. It called these “direct” (mainly from “heat, drought, and heavy

rain”), “mediated through natural systems” (e.g. “disease vectors, water-borne

diseases, and air pollution”) and “heavily mediated by human systems” (e.g.

“occupational impacts, undernutrition, and mental stress”). The first two

categories in this classification correspond with primary and secondary, but in

the third category only large-scale undernutrition would be classed as a tertiary effect,

as defined above.

In 2015 another major Lancet

report was released [31]. It proposed that impacts can be “direct” (e.g.

“heatwaves and extreme weather events such as a storm, forest fire, flood, or

drought”) or “indirectly mediated through the effects of climate change on

ecosystems economies, and social structure” (e.g. “agricultural losses and

changing patterns of disease” and “migration and conflict”). It thus grouped

“tertiary” effects with “secondary”, though it used neither term. A figure in

that paper which outlined the main direct and indirect effects focused solely

on what this essay suggests are more parsimoniously termed as

primary and secondary effects.

Conclusion

Apprehension of what I prefer to call the "tertiary" health effects of climate change has always been the primary motivator for my writing and researching on climate change (since my first letter, published in the Medical Journal of Australia, in 1991) [32]. I have argued above that these potential aspects were apparent in 1989, when articles first appeared mentioning all major "tertiary" components. I have also shown that the term "tertiary" was introduced in two papers published in 1993, already a quarter of a century ago.

Although there is increased recognition of these risks, the vast majority of the climate change and health literature continues to focus on issues such as heat, infectious diseases and allergies. Important as these issues are - and they are certainly are valid - I believe that their future burden of disease is likely to be dwarfed by that of the tertiary issues; conflict, population displacement and famine.

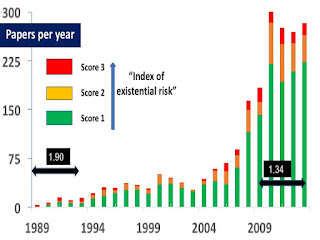

In 2014, in a chapter in my edited book called "Mental health, cognition and the challenge of climate change [33] I published a version of the following figure. In the next issue of the book the figure may be adapted, so that the label for the x axis (the horizontal axis) reads 2030. In 2014 I suggested that it might take until 2050 for the high burden of disease of the tertiary effects to be accepted, but that book was drafted before as much was reported about climate change and conflict in Syria, although an early paper was published in 2014 [34}.

I fear, given the events of 2018 - the fires, the floods, the hurricanes and typhoons, and the ongoing population displacement, as well as a gradually increasing acceptance of the role climate change plays in conflict - that the time in which the overwhelming risk of the tertiary health effects of climate will be widely understood may well be before 2050. On the other hand, the vast majority of articles in the climate and health field continue to completely ignore its existential risk [35].

|

| The proportional burden of disease of primary, secondary and tertiary effects (averaged over the 21st century) and the approximate time when these concepts and their relative burdens are accepted. |

A

powerful opposing force, however, is not just denial, nor just the

political factors that seek to repress any whiff of legal liability, and

hence minimize the risk of future reparations. One way to suppress such exploration is to refuse to fund research into the possible links. I think another reason has evolutionary roots. People like to portray themselves as “good",

even moral. Even the Nazis probably did .. so while on one hand

populations fully support policies that contribute to unspeakable

misery, on the other hand they deny the reality of the links between their behaviour and the more displaced effects, especially if they are harmful. If the

causes can be ascribed elsewhere ("local politics in Syria, not

environment") then we can feel better about ourselves. A good example is

that most Australians support offshore camps for asylum seekers,

claiming this is “humane” because “it saves lives at sea”. However, my

view is that the causation of this and other tertiary effects is multi-factorial. Developed countries have

largely contributed to climate change, but there are also many local factors

that have contributed to the war, famine, displacement, and the risks

people take which see some drown at sea.

However, the pendulum on the causes of the tertiary effects of climate change is currently too remote from recognition of the role that high-income countries have played in these catastrophes [36}, already and in future. And some people increasingly understand that climate change and other forms of planetary overload [37] pose profound risks to human well-being in high-income settings, such as 15 year old Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg, who also keenly appreciates the equity dimension (see figure).

|

| A tweet from 15 year old Greta Thurnberg, posted October 7, 2018 |

References

1. Robine, J.-M.; Cheung, S.; S, L.R.; Van Oyen H; Griffiths,

C.; Michel, J.-P.; Herrmann, F. Death toll exceeded 70,000 in Europe during the

summer of 2003. Comptes Rendus Biologies 331, 171-178 (2008).

2. Shaposhnikov, D.; Revich, B.; Bellander,T.; Bedada, G.B.;

Bottai, M.; Kharkova, T.; et al. Mortality related to air pollution with the

Moscow heatwave and wildfire of 2010. Epidemiology 25, 359-364 (2014).

3. Kang, S.; Eltahir, E.A.B. North China plain threatened by

deadly heatwaves due to climate change and irrigation. Nature Communications

(2018).

4. Pal, J.S.; Eltahir, E.A.B. Future temperature in southwest

asia projected to exceed a threshold for human adaptability. Nature Climate

Change 6, 197–200 (2016).

5. Sherwood, S.C.; Huber, M. An adaptability limit to climate

change due to heat stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (USA) 107, 9552-9555 (2010).

6. Martens, W.J.; Niessen, L.W.; Rotmans, J.; Jetten, T.H.;

McMichael, A.J. Potential impact of global climate change on malaria risk.

Environmental Health Perspectives 103, 458-464 (1995).

7. Siraj, A.S.; Santos-Vega, M.; Bouma, M.J.; Yadeta, D.;

Carrascal, D.R.; Pascual, M. Altitudinal changes in malaria incidence in

highlands of ethiopia and colombia. Science 343, 1154-1158 (2014).

8. Bhatt, S.; Weiss, D.J.; Cameron, E.; Bisanzio, D.; Mappin,

B.; Dalrymple, U.; Battle, K.E.; Moyes, C.L.; Henry, A.; Eckhoff, P.A., et al.

The effect of malaria control on pPasmodium falciparum in Africa between

2000 and 2015. Nature 526, 207-211 (2015).

9. Alonso, P., and A.M. Noor. The global fight against malaria is at crossroads. The

Lancet 390:10112 (2017).

10. Bergquist, Robert, Anna-Sofie

Stensgaard, and Laura Rinaldi. Vector-borne diseases in a warmer

world: Will they stay or will they go? Geospatial Health 13

(1): 699 (2018).

11.

Haines, A.; Epstein, P.R.; McMichael, A.J. Global health watch: Monitoring

impacts of environmental change. Lancet 342, 1464-1469 (1993).

12. Haines, A.; Parry, M.L.

Climate change and human health. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine

86, 707-711 (1993).

13. McMichael, A.J.; Haines, A.;

Slooff, R.; Kovats, S. Climate change and human health. World Health

Organization: Geneva (1996).

14. Patz, J.A.; McGeehin, M.A.; Bernard, S.M.; Ebi, K.L.; Epstein,

P.R.; Grambsch, A.; Gubler, D.J.; Reiter, P.; Romieu, I.; Rose, J.B., et al.

The potential health impacts of climate variability and change for the United States: Executive summary of the report of the health sector of the U.S.

National Assessment. Environmental Health Perspectives 108, 367-376 (2000).

15. Anonymous. Health

in the greenhouse. Lancet 333:819-820 (1989).

16.

Leaf, A. Potential health effects of

global climatic and environmental changes. The New England

Journal of Medicine 321 (23):1577-1583 (1989).

17.

Kelley, C. P., Mohtadi, S., Cane, M.A., Seager, R. and

Kushnir, Y. Climate change in the Fertile Crescent and implications

of the recent Syrian drought. Proceedings of the National

Academy of Sciences (USA) 112 (11):3241-3246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421533112 (2015).

18. Anonymous. Syria: A health

crisis too great to ignore. The Lancet 388, 2 (2016).

19. Selby, J.; Dahi, O.S.; Fröhlich, C.; Hulme, M. Climate change

and the Syrian civil war revisited. Political Geography (2017).

20. Ide, T. Climate war in the Middle East? Drought, the Syrian Civil War and the

state of climate-conflict research. Current Climate Change

Reports:1-8; doi: 10.1007/s40641-018-0115-0. doi:

10.1007/s40641-018-0115-0 (2018).

21. Kovats, R.S.; Hajat, S. Heat

stress and public health: A critical review. Annual Review of Public Health 29, 41-55 (2008).

23. Schleussner, C.-F.; Donges, J.F.; Donner, R.V.; Schellnhuber,

H.J. Armed-conflict risks enhanced by climate-related disasters in ethnically

fractionalized countries. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,

113, 9216-9221 (2016).

24. Kishore, N.; Marqués, D.; Mahmud, A.; Kiang, M.V.; Rodriguez,

I.; Fuller, A.; Ebner, P.; Sorensen, C.; Racy, F.; Lemery, J., et al. Mortality

in Puerto Rico after hurricane Maria. New England Journal of Medicine,

doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1803972 (2018).

25. Butler, C.D.; Corvalan, C.F.; Koren, H.S. Human health,

well-being and global ecological scenarios. Ecosystems, 8, 153-162 (2005).

26. Confalonieri, U.; Menne, B.; Akhtar, R.; Ebi, K.L.; Hauengue,

M.; Kovats, R.S.; Revich, B.; Woodward, A.; Abeku, T.; Alam, M., et al. Human

health. In Climate change 2007: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability.

Contribution of working group II to the fourth assessment report of the

intergovernmental panel on climate change, Parry, M.L.; Canziani, O.F.;

Palutikof, J.P.; Linden, P.J.v.d.; Hanson, C.E., Eds. Cambridge University

Press: Cambridge, UK,, 2007; pp 391-431 (2007).

27. Butler, C.D.; Harley, D. The climate crisis, global health,

and the medical response Postgraduate Medical Journal 86, 230-234 (2010).

29. Portier, C.J.; Thigpen Tart, K.; Carter, S.R.; Dilworth, C.H.;

Grambsch, A.E.; Gohlke, J.; Hess, J.; Howard, S.N.; Luber, G.; Lutz, J.T., et

al. A human health perspective on climate change: A report outlining the

research needs on the human health effects of climate change. Research triangle

park, NC: Environmental Health Perspectives / National Institute of

Environmental Health Sciences. doi:10.1289/ehp.1002272 available:

www.niehs.nih.gov/climatereport (2010).

30. Smith, K.; Woodward, A.; Campbell-Lendrum, D.; Chadee, D.;

Honda, Y.; Liu, Q.; Olwoch, J.; Revich, B.; Sauerborn, R.; Aranda, C., et al.

Human health: Impacts, adaptation, and co-benefits. In Climate change 2014:

Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability, contribution of working group ii to the

fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change,

Field, C.B.; Barros, V.; Dokken, D.J., Eds. Cambridge University Press:

Cambridge and New York; pp 709-754 (2014).

31. Watts, N.; Adger, W.N.; Agnolucci, P.; Blackstock, J.; Byass,

P.; Cai, W.; Chaytor, S.; Colbourn, T.; Collins, M.; Cooper, A., et al. Health

and climate change: Policy responses to protect public health. The Lancet

386, 1861–1914 (2015).

32. Butler, C.D. Global warming, ecological destruction and human health. Medical Journal of Australia 155:351 (1991)

32. Butler, C.D., Bowles, D.C; McIver, L., and Page, L. Mental health, cognition and the challenge of climate change. In Climate Change and Global Health, edited by C.D. Butler, 251-259. Wallingford, UK: CABI. (2014).

34. Gleick, P.H. Water, drought, climate change, and conflict in Syria. Weather, Climate, and Society 6 (3):331-340. doi: 10.1175/wcas-d-13-00059.1 (2014).

35. Butler, C. D. Climate change, health and existential risks to civilization: a comprehensive review (1989-2013). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health (under review).

36. Butler, C.D. "Regional overload” as an indicator of profound risk: a plea for the public health community to awaken. In Medicines for the Anthropocene: Health on a Finite Planet, edited by S. Quilley and K. Zywert. Toronto, Canada, University of Toronto Press, 2019 (in press).

37. Butler, C.D. Planetary overload, limits to growth and health. Current Environmental Health Reports 3 (4):360-369 (2016)