In June 2019 the 16th Sakyadhita conference will be held, for the first time ever in Australia. See

here for details. These are large meetings; the

previous one,

held in Hong Kong in 2017, attracted about 800 attendees from 31

countries. BODHI Australia will be attending this meeting, represented

by at least 4 committee members and one partner, Karunadeepa. Below is

the summary of our paper, and below that is our current draft of the

full paper.

The paper is designed to be read; some repetition is deliberate

Authors: Maxine Ross, Karunadeepa, Emilia Della Torre; Colin D. Butler

Summary:

In 1956 the great reformer Dr Bhimrao Ambedkar led, in Nagpur, India, a

mass conversion to Buddhism, involving at least 300,000 people.

Millions more have since converted in an ongoing social movement, still

keenly needed, reaching for greater justice in India, particularly for

women, and particularly for Dalits, once called “untouchables”. Since

2005 the NGO BODHI Australia (founded in 1989) has supported the work of

a team led by

Karunadeepa,

a Dalit whose grandfather took part in the historic Nagpur conversion,

and who for decades has worked for an Indian NGO, based in Pune, India,

itself largely supported by the UK Karuna Trust, allied with Triratna,

whose founder (Venerable Sangharakshita) first met Dr Ambedkar in 1952.

The work BODHI Australia has supported with Karunadeepa and her team

mainly seeks to enhance the life-chances of slum-dwellers, especially

migrants from rural Maharashtra (not necessarily Dalit, nor Buddhist) by

improving education, health and awareness of family planning. In 2017

Karunadeepa, with Dalit colleagues, started to develop a new NGO, the

Bahujan Hitay Pune Project, entirely governed by Dalit women, which will

extend and deepen this work, but which also presents new challenges. In

this talk, Karunadeepa, during her first visit to Australia, will

discuss these activities, together with representatives of BODHI

Australia. BODHI’s work to support Dalit-led and other

development-promoting projects in India may seem a drop but can also be

seen as a key to inspire, to resist oppression, to support development

and to assist escape from poverty and vulnerability.

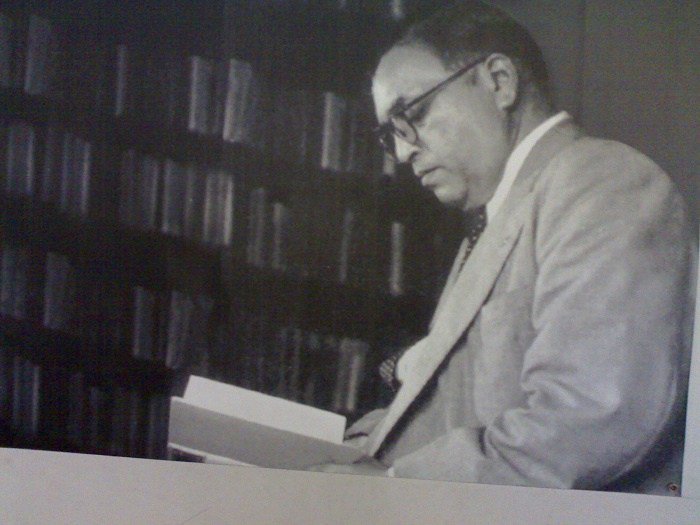

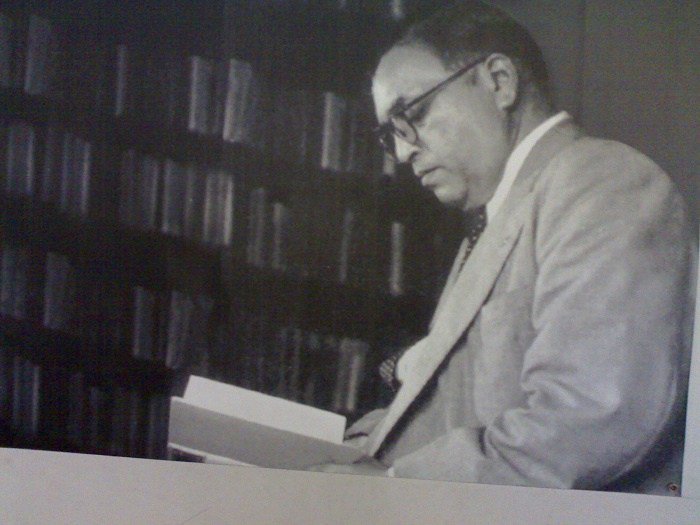

Dr Ambedkar. https://www.culturalindia.net/reformers/br-ambedkar.html original source unknown

Full paper:

-->

This paper starts by acknowledging the traditional owners of the land this conference is held on, the

Gundungurra, the Indigenous people who have thrived on this continent for

at least 65,000

years. The authors of this paper are all apprentices of dharma. Between

us, we have been exposed to about two centuries of close contact with

Buddhism. One of us (Karunadeepa) was born Buddhist. However, none of us

claim, or admit, deep knowledge of Buddhist scholarship. We thank the

organisers of this historic conference for the opportunity to speak and

to be published in this setting, alongside the work of people with far

more scholarly knowledge of Buddhism than we will ever have.

The main motivation for this talk and essay is to provide information about the work of some followers (in Pune, India) of

Dr Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, who lived in India from 1891 until 1956. Dr Ambedkar was 65 years old when he died, coinciding with the

Buddha Jayanti festival,

to honour Buddhism’s 2500th year. The Dalai Lama first arrived in

India, mainly to attend this celebration, only a few days before Dr

Ambedkar died.

|

Add caption

The traditional Buddhist dharma wheel,

representing interdependence and liberation, was added to the Indian national

flag at Dr. Ambedkar’s suggestion. Here it is on a stamp, issued to celebrate 2500 years of Buddhism. Source

|

-->

While three of us were not born Buddhist, an

important reason for our attraction to it is its links with social

justice, or fairness, including its rejection of the principle that

hereditarily transmitted inequality is legitimate. A basic teaching of

many religions (maybe all of them) is the principle of cause and effect.

In both Buddhism and Hinduism this principle is called karma, yet the

dominant group in each of these two faiths, otherwise quite similar,

appears to have a drastically different interpretation of this

principle. Because we are not scholars, even more than from lack of

time, we cannot trace these differences to early teachings. Instead, the

observations in this paper are based mainly on our own personal

experience, and our understanding of world events, both today and in the

fairly recent past.

Whether or not there is a future life, the three

authors of this paper, not born Buddhist, have all been, at various

times, intensely moved by the unfairness of the social world, as was Dr

Ambedkar, born a Hindu, but who converted to Buddhism in October 1956.

This was in Nagpur, Maharashtra, in central India, at a mass gathering

attended by over 300,000 people, one of whom was a grandfather of the

fourth author of this paper,

Karunadeepa, the only one of us who was born Buddhist.

In

Australia, even among those of European descent, much inequality is

passed through the generations, and along family lines, by privilege and

unequal access to opportunity. Many people who are wealthy went to

exclusive, expensive schools, where, in time, they send their own

children. It is well-known, and not just allegation, that many rich

people do not pay a fair share of tax. Mackenzie Bezos, the soon to be

divorced wife of Jeff Bezos, the founder of the company Amazon, is

reported to be due to receive almost US$70 billion in her divorce

settlement. In so doing, she will become the richest woman in the world.

Bezos, himself, is reported to have humble origins, the son of a

teenage mother and a father who has been described as “deadbeat”. But

his example of transition from hardship to fabulous wealth is more the

exception than the rule.

Dr Ambedkar, who served as Law Minister

in the first Indian government in 1947, was also exceptional. This was

not through extraordinary entrepreneurial skills and alleged

“robotization” of employees (the Bezos route), but from an vigorous and

courageous intellect, some protection in childhood (due to descent from

several generations of soldiers, including his father who rose to be an

officer, in an army whose British leaders were far less caste-conscious

than most Indians) (1) and hard work. Timing and history was also important.

Ambedkar became a leading public figure through his central role in the

struggle for Indian independence from Britain, recently reported as

plundering the equivalent of $45 trillion from India during its long

occupation (2).

We said that Dr Ambedkar was born Hindu. More

accurately, as a member of the Mahar caste, he was born “untouchable”,

meaning that close contact with him (even if indirect) was considered,

by orthodox Hindus, to pollute or contaminate those who were

conditioned, usually since birth, to consider themselves “higher born”,

such as Brahmins.

For example, as a schoolboy, Ambedkar not only

had to sit in a separate section at school (sometimes outside) but could

not touch the tap if he was thirsty. In order to drink, a peon,

considered “touchable” had to be found to turn it on.

Once, while

travelling to visit his father, Ambedkar, aged 9, with a brother and

two young nephews, all children, were stranded for over an hour at the

station (following their first ever train ride), waiting for a servant that

never arrived. The stationmaster was at first sympathetic to four

well-dressed children, until discovering their lowly caste. Eventually,

however, he helped them to find, with difficulty, a bullock cart driver,

who agreed to take them to their destination, for twice the normal fee.

But this was on condition that the children acted as driver while the

driver walked, for fear of caste “pollution”. En route (on an overnight

journey), as part of a harrowing ordeal, they were refused water (3).

Reflecting on this, Ambedkar wrote: “it left an

indelible impression .. before this incident occurred, I knew that I was an

untouchable, and that untouchables were subjected to certain indignities and

discriminations. All this I knew.

But this incident gave me a shock such as I had never received before, and it

made me think about untouchability--which, before this incident happened, was

with me a matter of course, as it is with many touchables as well as the

untouchables.

To non-Indigenous Australians the

idea of caste might seem ludicrous. But there are traces of the caste

system here too. We see it in films of past European royalty, and there

are echoes in Australia’s treatment of asylum seekers and in the

different punishments for white collar (executive) crime compared to

those committed by blue collar wearers (working class). Discrimination

based on skin colour, religion or age is officially banned (but

persists) in Australia, though discrimination based on ability to pay is

everywhere. We are nor arguing against laws and punishment, we are

instead proclaiming support for the need for a fairer world, including

of more equal opportunity.

Today, in India, the injustice of caste is

milder, especially in urban areas, than in Dr Ambedkar’s time. This is

partly due to Dr Ambedkar, partly to increased Westernisation of

affluent Indians, and partly the work of liberal Hindus, such as the

Ramakrishna mission. But chiefly, it is from the struggle and

inspiration of tens of millions of people (sometimes called Dalits) who

have renounced the legitimacy of caste as a concept. Karma may still

exist, but it no longer can be unquestioningly interpreted as meaning,

at least in India, that parental status and income completely determines

one’s life course, though, naturally, the culture that children are

reared in has a powerful “throwing” effect.

Many injustices still

exist, in India and elsewhere, including for millions of “tribal”

people. One group, seeking to reduce this injustice, and inspired by the

teaching and legacy of Dr Ambedkar, is led by Karunadeepa. In 2017,

with colleagues, almost all of whom are women, Karunadeepa started to

develop a new non-government organization (NGO), called the

Bahujan Hitay Pune Project.

Since 1982, this work has been undertaken under the umbrella of a

larger NGO, the Trailokya Baudha Maha Sangh Gana, but the time has come

for a new, legally distinct group.

Bahujan refers to the people

in the majority, meaning in India, “Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes

and Other Backward Castes”. Bahujan Hitay roughly translates as “for the

welfare of many”. The work of the Bahujan Hitay Pune Project is

principally with disadvantaged slum dwellers (scheduled castes and

scheduled tribes) in this city of about six million, in the sprawling

state of Maharashtra, parts of which are afflicted by drought and

accompanying desperation, including farmer suicide. Consequently, many

people migrate to Pune, seeking better conditions.

This work in Pune has, since 1982, been supported by the

Karuna Trust

a British charity founded by the late Ven Sangharakshita, who, as young

man seeking to work for the good of Buddhism, based mainly in

Kalimpong, in the Himalayan foothills, met Dr Ambedkar three times,

including shortly before his conversion (4). Since 2005, this work led

by Karunadeepa has also been supported by two NGOs with an Australian

connection. These NGOs (

BODHI and

BODHI Australia) were co-founded by

Colin Butler and his late wife Susan, in 1989. Since then, these groups

have raised and distributed about A$0.5M to partners in six countries in

Asia, mostly in India. The acronym means Benevolent Organisation for

Development, Health and Insight. BODHI Australia also helps to support

the Aryaloka Education Society, a Dalit-led NGO, based in Nagpur, which

teaches basic computing skills, mostly to young women from poor

villages.

In this talk, Karunadeepa, during her first visit to

Australia, will discuss some of the activities of the Bahujan Hitay Pune

Project. Four members of BODHI Australia’s committee, in addition to

Karunadeepa, are attending the whole conference, and they hope to learn

from and gain inspiration and encouragement from other individuals or

NGOs engaged in similar development work.

|

| Mrs Rubina Khan who trains slum dwellers in beauty therapy and hairdressing trainer. With permission.These three photos were taken in Pune, Maharashtra, India, in March 2018 (by Colin Butler) |

|

| Mrs Sushma Chavan, an assistant teacher in the an assistant teacher at the Hadaspar balwadi (kindergarten) (Pune), with her two daughters. |

|

|

|

| The boy (Aniketh) is soon to have surgery - provided for free by the Indian government. |

Whether or not there is

a future life, we believe that the creation of good karma is important

to try to reduce suffering, in this life. In our understanding of

Buddhism, core values are compassion (karuna) and wisdom (panna or

prajna), while the first Noble truth refers to the reality of suffering,

not only of the perceiver, but also of others – human, animal and even

Nature herself.

In the three decades of BODHI’s work the barriers

facing partner organizations, in order to receive foreign funds have

worsened. This steepens the challenge to reach the poorest people and to

promote genuinely long-lasting development. But there is still great

need. We ask for your support, either directly, or in many other ways.

References

2. Patnaik U.

How the British impoverished India. Hindustan Times. 2018.

3. Ambedkar BR.

Waiting for a visa. In: Moon V, editor. Dr Babasaheb

Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches. Bombay, India: Education Department,

Government of Maharashtra; 1993.

4. Sangharakshita U. Ambedkar and Buddhism: Windhorse Publications; 1986. Free

pdf of book

here.

-->